All along the ivory tower

/Next month a march for science has been called to protest against the anti-science positions of the new US government. I decided to mark the occasion with a little motivational illustration and I will probably join the NYC march myself on Saturday the 22nd of April (Earth Day). Some scientists, like geologist Robert S. Young, criticised the idea of a march for science arguing that it will just reinforce the idea of science as a ‘liberal’ enclave:

Scientists marching in opposition to a newly elected Republican president will only cement the divide. The solution here is not mass spectacle, but an increased effort to communicate directly with those who do not understand the degree to which the changing climate is already affecting their lives. We need storytellers, not marchers.

As a scientist communicator I couldn’t agree more with the latter point but I still think that anything that takes scientists out in the streets is a good thing. I think a deeper problem, partly responsible for the spread of anti-science movements, is that for decades our academic system has more or less openly discouraged any engagement with social issues, such as politics. Anything that is not devoted to the pursuit of pure knowledge is considered at best a pastime, at worse a sign that you are not serious enough about your research. The result is that scientists, in particular, are often a very insular community, perceived (and depicted) as charmingly detached from everyday problems. It certainly doesn’t help that in this country the ‘campus’ model for universities has created a geographical segregation, in addition to a cultural one. This concept is beautifully expressed with the metaphor of the ‘ivory tower’.

I think this divide is particularly relevant for my own research in science comics. I have been lucky enough to receive the support of one of the most respectable academic institutions and I am surrounded by enlightened people who understand what I am trying to do. However, there is no point in denying that in popular culture comics are still very much associated with the idea of cheap entertainment. The result is that there is often a huge gap between the way I think and write about comics in my research, and the way they are actually used in everyday science communication. Many of the studies that I have been reading in the past few months still praise comics mostly for being ‘fun’, ‘easy’ and particularly suitable 'for children’. I know some of these papers are outdated but somehow it is still painful to read statements such as: “unlike the more formal textbook, comic strips are more casual and consumable: they can be cut apart, drawn on, and colored with more freedom.” (J.R. Richie quoted in Gonzáles-Espada 2003).

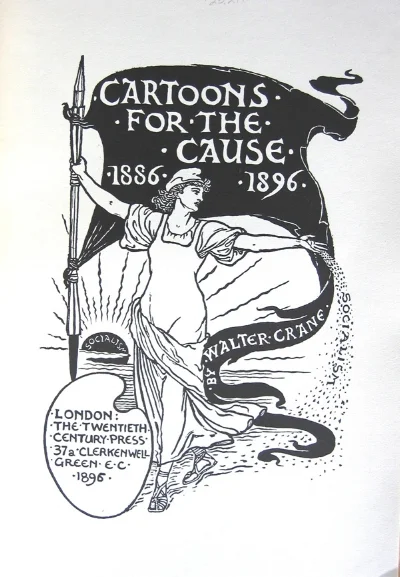

But then again, why not? If it helps demystify science and promote public engagement go ahead and cut my comics apart, why should I care? The truth is that I myself fall victim to the highbrow culture of academia and I am eager to see comics recognized as the powerful and versatile medium that I think they are. But I have to remind myself that for the purpose of science communication (intended as 'public engagement' and not simply as 'education' - see Meyer 2016) it may actually be useful to embrace the tradition of comics as a cheap, disposable, lowbrow medium. Although not all comics have to be fun, it is also important to recognize that comics can be incredibly fun! Throughout history cartoons have proven an excellent way to challenge authority and engage with the public (all things that would greatly improve scientific debate). This is why comix and zines have been the medium of choice for countercultures all around the world. According to art scholar Roger Sabin (1996):

The comic's exclusion from the art establishment enables it to eschew the dampening appraisal of art criticism. Moreover, its association with street culture gives it a certain edge, which many contemporary artists have vainly attempted to transfer to the gallery. Whereas fine art can only send shocks through the art world, comics - available to a far broader audience - are still regarded as dangerous enough to be clamped down on intermittently. (p. 236)

The ultimate question is: will comics be able to become ‘respectable’ enough to be allowed in scientific circles without losing their edginess and irreverence? It’s not an easy balance but, if achieved, it would make comics the ideal medium to cross the walls of the ivory tower and maybe help the many scientists who are planning to run for office. Because of their history, I think that a full analysis of 'science comics' should not simply focus on their educational potential but also address their role in changing the perception of science in our society.

Walter Crane (1896) Cover for Cartoons for the Cause

REFERENCES:

González-Espada, W.J. (2003). Integrating physical science and the graphic arts with scientifically accurate comic strips: rationale, description and implementation.

Meyer, G. (2016). In science communication, why does the idea of a public deficit always return? Public Underst. Sci. 25, 433–446.

Sabin, R. (1996). Comics, comix and graphic novels (Phaidon).

Williams, R. (2008). Image, Text, and Story: Comics and Graphic Novels in the Classroom. Art Educ. 13–19.

Young, R.S. (2017). A Scientists’ March on Washington Is a Bad Idea. N. Y. Times.